Ever noticed the gap between lightning and thunder during a storm? That pause is the speed of sound in action. But what exactly does it mean, and why does sound travel differently through air, water, or metal? Honestly, it’s one of those things we all know exists but rarely think about. Let’s break it down in a way that’s kind of fun and easy to follow.

The speed of sound is more than just a number. It’s about vibrating molecules, waves moving through matter, and physics that directly affects our daily life. Let’s explore it together.

Speed of Sound Explained

So what is the speed of sound? Simply put, it’s how fast a sound wave moves through a medium. Most often, we think of air, but sound can travel through water, metal, or almost any solid or liquid.

Imagine dropping a pebble in a pond. The ripples spread outward. Sound works similarly, but instead of water, tiny particles vibrate and pass the energy along. The “speed” refers to how fast the ripple moves.

In air at room temperature, sound travels around 343 meters per second. That’s fast but not instant, which is why you notice thunder after lightning. Temperature, pressure, and humidity all affect this speed slightly.

Factors That Affect the Speed of Sound

Why does sound travel faster in some materials than others? It’s all about how tightly packed the particles are and how easily they vibrate.

-

Air: Molecules are spread out, so sound moves moderately fast.

-

Water: Molecules are denser, allowing sound to travel faster. Underwater sounds seem almost immediate.

-

Metal: Extremely dense and stiff. Sound can travel five times faster than in air. Tap a metal pole, and you hear it instantly from the other end.

Temperature matters too. Warmer air makes molecules move faster, increasing the speed of sound. Cold air slows it down. That’s why early morning fog feels quiet—the sound moves slightly slower.

History of Measuring the Speed of Sound

For centuries, humans didn’t know how fast sound traveled. Ancient thinkers like Aristotle assumed sound was almost instantaneous. Imagine that.

By the 17th century, scientists started measuring it using cannons. They observed the flash and timed the boom. This method was basic but surprisingly effective. Over time, accurate measurements became crucial for navigation, military, music, and science.

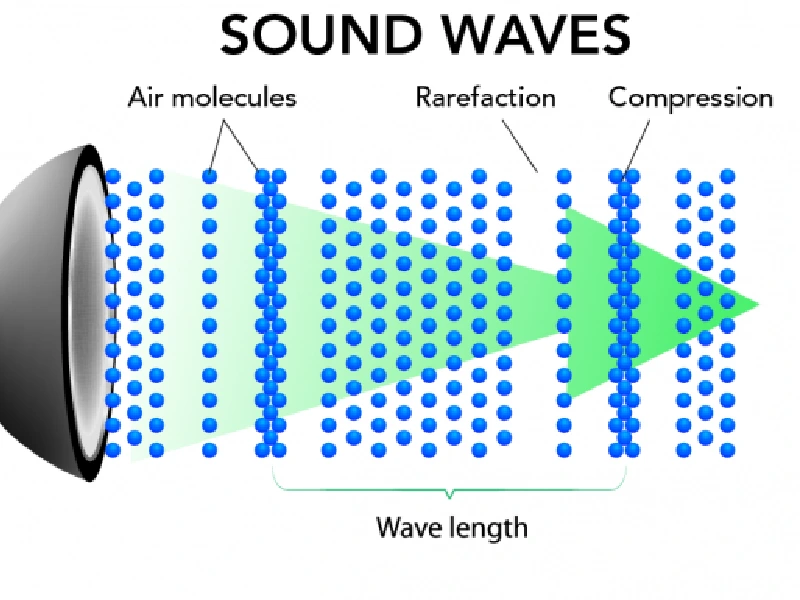

How Sound Travels: A Simple Explanation

Sound is a mechanical wave, meaning it needs a medium. Unlike light, it cannot travel in a vacuum.

The process works like this:

-

A source creates vibrations, such as your voice or a drum.

-

Vibrations push nearby particles.

-

Each particle passes the vibration to the next.

-

This chain reaction spreads outward as a wave.

The particles themselves don’t move far; they just vibrate. It’s like a stadium wave at a football game. You stay seated, but the wave travels around the stadium.

Speed of Sound in Different Materials

Here’s a quick reference for the speed of sound in various materials:

| Material | Speed of Sound | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Air (20°C) | 343 m/s | Everyday air |

| Water (20°C) | 1482 m/s | Underwater faster speed |

| Steel | 5960 m/s | Extremely fast due to stiffness |

| Helium | 965 m/s | Makes your voice high-pitched |

| Vacuum | 0 m/s | Sound cannot travel |

Different materials affect sound travel dramatically, which is why engineers, divers, and musicians pay attention to it.

Breaking the Sound Barrier: Supersonic Speed

Ever heard a jet break the sound barrier? The loud boom you hear is a sonic boom. It happens when something moves faster than sound in the air. Chuck Yeager famously broke the sound barrier in 1947.

When an object moves faster than sound, air molecules can’t get out of the way fast enough. The sudden compression forms a shock wave, producing the boom. Pilots often hear it after they’re past the point of breaking the barrier.

Real-Life Examples of Sound Speed

The speed of sound affects everyday life more than we realize:

-

Thunderstorms: Count the seconds between lightning and thunder to estimate distance.

-

Concerts: In large stadiums, sound can echo, and speaker delays are adjusted for speed.

-

Underwater Communication: Submarines use sonar to locate objects quickly.

-

Movies and Games: Sound designers adjust speed to create dramatic effects.

How Humans Perceive Sound

Humans often don’t notice small changes in sound speed. A slight difference in air speed is barely detectable. But in water or solids, the difference is noticeable.

This explains why fireworks or distant explosions sometimes seem out of sync. Our brains assume sound is instant, but physics proves otherwise.

Fun Anecdote About Sound

Once, while camping in the mountains, I watched a thunderstorm. I counted the seconds between lightning and thunder and estimated the storm’s distance. It turned a normal storm into a mini physics lesson. Little moments like this remind us how everyday sound connects to science.

Practical Uses of Sound Speed

Knowing the speed of sound is useful in science and technology:

-

Weather Science: Measures air temperature and pressure indirectly.

-

Oceanography: Helps submarines and sonar systems function.

-

Engineering: Tests material properties and safety.

-

Medicine: Ultrasound imaging depends entirely on sound speed in tissues.

FAQs

Does sound travel faster in hot air?

Yes, warmer air speeds up molecular vibrations, increasing sound speed.

Can sound travel in space?

No. Space is a vacuum. Sound needs particles to vibrate.

Why does metal carry sound better than air?

Metal is dense and stiff. Vibrations transmit efficiently.

What is the fastest speed of sound in natural materials?

Diamond is among the fastest at around 12,000 m/s.

How is the speed of sound measured today?

Modern methods use precise microphones, lasers, and timing equipment. Early methods used cannons and stopwatches.

Fun Fact: Helium and Your Voice

Inhaling helium temporarily changes the speed of sound around your vocal cords, making your voice high-pitched. It’s a simple physics trick, but always use it safely.

Conclusion

Sound speed isn’t just physics—it’s a part of daily life. From thunderstorms to concerts, submarines to jet planes, it shapes how we hear and experience the world. Next time you hear thunder or a jet zooms overhead, remember those tiny vibrating molecules doing their work. Sound is science, mystery, and everyday magic all in one.